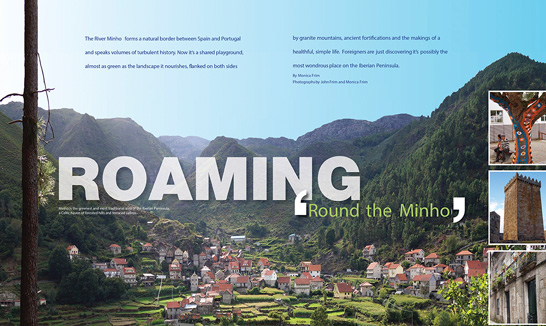

Roaming "Round the Minho"

Photography by John Frim and Monica Frim

The Iberian Peninsula has long been one of Europe's most popular destinations, known best for the jam-packed beaches of Portugal's Algarve or Spain's glittering Mediterranean resorts. But if you want to capture the essence of both countries without a fight for towel space, there's a nugget of calm in the northwestern crook of the peninsula that perfectly captures the spirit of Iberia and all its bounty without the crowds.

Here the River Minho (or Miño in Spanish) tears a diagonal strip from the Galician town of Lugo in Spain to the Atlantic Ocean 230 miles to the southwest. The Minho's final 50 miles, shared by both Spain and Portugal, are lined with ancient walled villages that topple along the riverside before giving way to inland farms and vineyards. Primitive hiking trails lead to abandoned monasteries on rock-ribbed mountains, panoramic views of mossy granite villages unfold among winding trails and leafy lanes culminate at lookouts with views that, in one direction, stretch all the way to the Atlantic Ocean.

The best part is that while Minho territory is a relative newbie on the Iberian tourist circuit, it's arguably the most scenic. The fact that it serves as a gateway to some of Europe's most famous landmarks is gravy. You can plant yourself in any hotel along the Spanish-Portuguese border, yet take in a panoply of adventures and attractions in both countries, all within an hour's drive in any direction.

Head north, and you'll reach Spain's Santiago de Compostela with its revered tomb of James the Apostle. To the south you'll find another pilgrimage site, the Santuário de Bom Jesús on the outskirts of Braga. It is reputedly the most photographed church in Portugal, famous for its zigzagging staircase and 17 landings. Go west and you'll see the Atlantic Ocean blowing a salty fringe into the River Minho's pine-rimmed estuary, a place where sandy river beaches offer both shade and sunshine. South of the estuary, endless beaches vary with the moods of the Atlantic — from quiet ripples in coves to solid walls of pummeling swells — the stuff of world-class surfers' dreams. And in the east, Portugal's only national park, the Peneda-Gerês, protects a bucolic mountain life that centers around transhumance (the seasonal moving of livestock to remote granite villages) and the preservation of rare, endemic animals such as wild Garrano ponies, Laboreiro sheep dogs and Cachena cattle.

Throughout the region, traditions endure in the form of weekly markets that probably haven't changed much since the Middle Ages, and frenzied "carnavales" hearken back to Celtic roots as revelers in handmade costumes and masks celebrate the reawakening of earth with an interfusion of music, food and frivolity. Each town has its own attractions, culinary specialties and folkloric art, but all are bound by lore and ritual that somehow meld with modern conveniences and state-of-the-art galleries, museums and hotels. Taken alone or in any combination, the Minho area's tranquil offerings make for an effortless vacation that refreshes, revitalizes and relaxes, regardless of how much (or how little) you pack into your days.

Our first day we did nothing more than acquaint ourselves with the lay of our lodging, a delightful wellspring of Scandinavian design that sits like a modern white sculpture of largely horizontal proportions in the viny green landscape of Vila Nova de Cerveira, about an hour's drive north of Porto. We ambled about the Hotel Minho's gardens, cupped a handful of pool water to test its temperature (cold) and walked the length of the uninterrupted outside balcony that looked over the hotel's rooftop gardens with distant views sweeping out to the misty green hills of Spain in one direction and northern Portugal in the other. Back inside the hotel we donned slippers and bathrobes in preparation for the hotel's most seminal service — a spa treatment that draws inspiration from the region's alvarinho grapes and honey to treat a variety of ailments, from stress to jet lag and post-flight bloating.

It's a known fact that flights across multiple time zones, especially the eastbound and overnight type, wreak havoc with the body's circadian rhythm, stiffen the muscles and fog up the mind. The Hotel Minho's spa features a special jetlag massage — a 20-minute soak in a gently bubbling tub of saltwater and seaweed — that effortlessly seems to melt off the jet lag and restore the internal clock. We coupled it with a Vichy hydromassage, which uses an exfoliating scrub of grape seeds, sea salt and cold-pressed grape seed oil to sandpaper the body into a shiny state of wellness and remind the spirit of renewal. In the name of research — and because we were putty under the masseuses' skilled hands — we further tested the Hotel Minho's reputation for regional spa superiority with more couples' treatments with the signature honey massage for me and the deep-tissue Melissa massage for my husband. Next came heaven in a hamam (Turkish bath) followed by a soak in the hot tub atop a gently bubbling bed made of tubular steel.

That night we slept like hibernating bears, waking early the next morning pumped and primed for the first day of an intensive five-day sightseeing program that involved a private limo service with a dapper guide and driver. Francisco came with impeccable qualifications — an encyclopedic knowledge of Spain and Portugal with a charming demeanor that included daily draughts of wit and humor delivered with note-perfect timing. His devastating good looks were a fine bonus.

A typical white September fog had rolled in from the Atlantic Ocean, hovering like angel hair on Christmas trees. "No worries, no worries," said Francisco as he ushered us into his Mercedes. "In two hours the sun will have burned it all off . . . and if it doesn't . . . well, then you will simply have to imagine what I am describing. But for now just enjoy how beautiful the fog looks."

It did indeed. At the mouth of the River Minho, on the Spanish/Galician side, Mount Tecla poked through frothy brume with an auroral glow that conjured up ancient Galician legends of "feiticeiras" (witches), mermen and strange mythological figures that were said to be lurking in the Minho basin. But on clear days, fantasy gives way to history as the sun reveals hilltop monuments and other remnants of various civilizations that battled throughout the centuries for control of the land. Hairpin bends lead to Tecla's ancient Celtic hill-fort and stunning views over Portugal as well as the River Minho's breathtaking convergence with the Atlantic Ocean.

The shared history of Spain and Portugal has been cobbled together by various conquerors of the Iberian Peninsula. Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Suevi, Visigoths and Moors all stamped the grounds with their own brands of architecture, habits and warfare. Alliances were forged and dismantled, kingdoms sprouted then merged with other kingdoms in the aftermath of rebellions or intermarriages that reshaped the political landscape. The River Minho roiled with the blood of marauding armies then eventually settled into an enviable current of calm with the people on both sides building bridges — both fi gurative and real — paddling their boats and resuming friendly visits back and forth like long-lost relatives after a family feud.

Why wouldn't they? Today Portugal and Spain have similar governments and similar interests. The people cross back and forth across the river into each other's countries like neighbors sharing a backyard barbecue. There are no border formalities, no checkpoints, no passport requirements and the currency is the same. Even the languages are similar, which is one reason why Galicians claim to have more in common with the Portuguese than they do with the rest of Spain.

Yet icons of erstwhile discord endure. The most notable is at Valença do Minho, an impressive fortifi ed town on the River Minho that serves as a major entry point from Spain. The fi rst walls stem from the 13th century with additional fortifi cations added mostly during the 17th and 18th centuries to repel Spanish and French incursions. Two fortresses complete with bastions, watchtowers, turrets, impressive gateways and hulking bulwarks stand at the endpoints of medieval cobblestone lanes. In between, Gothic and Romanesque churches endure alongside Manueline manors and stands of towels and linens — booty for modern Spanish invaders armed with wallet fodder. Boutiques and souvenir stalls are crammed together like shot in a musket. We joined the Spanish incursion by day but, once inside the gates, abandoned any urge to shop in favor of ambling among landscaped battlements, decommissioned cannons, churches, statuary and an ancient Roman road marker that, in the first century AD, marked the distance of 42 miles on the road from Braga to Tui. True to Francisco's word, by noon the sun was bathing the bulwarks and surrounding cornfields with a golden light.

When night falls the Spanish shopping brigade beats a retreat to the tapas bars in the Galician town of Tui across the river along with a goodly Portuguese platoon. It seems an equitable trade — towels for tapas — that bolsters a respectable border economy and keeps relationships between Spain and Portugal warm and friendly. Passage is quick and easy by car (or you could walk it in less than half an hour), courtesy of two international bridges. The more famous of the two is a kind of horizontal Eiffel Tower, built in 1884 by the Riojan engineer Pelayo Mancebo (not by Gustave Eiffel as is sometimes reported). The modern bridge was built in the 1990s.

Tui's most distinguishing feature is the town's illuminated hilltop cathedral — a crenellated study of Gothic and Romanesque elements. Viewed from the fortifications of Valença or from one of the bridges that connect the two medieval towns, the soft lights of the cathedral cast a warm glow over the River Minho, outshining the twinkling lights of street lamps and other buildings. Some of Tui's most significant attractions — tapas bars, churches and ancient granite buildings — line the narrow streets that wind through the historic quarter and down the hillside toward the river. Tui may not be Paris, but for tired and hungry cross-border shoppers, it's a dollop of Galician authenticity.

Thirty miles to the west, the fishing village of Caminha is situated at the confluence of the Minho and Coura Rivers, a stone's throw from the Atlantic Ocean, and with two beaches to jibe. Here is the gateway to the Costa Verde, the densely vegetated stretch of green coast that champions beaches, fishing, golf and the odd casino. Caminha itself has a quiet charm that's a far cry from its life in the 1700s as a rollicking port. These days high times amount to nibbling on patiscos (tapas) with the locals at the open-air cafés around the central square or ambling among charming attractions such as the town hall, Renaissance clock tower and raised circular fountain. But if you're looking for edgier attractions, the church is possibly your best bet. There, perched at the edge of the roof among an array of gargoyles and chimeras in typically frightening mien, the stone caricature of a Portuguese man — or woman, depending on who's telling the story — strikes what, in polite company, can best be called a potty pose, with bare buttocks and a salient smirk aimed at snubbing an adversary from across the river.

Between Caminha and Melgaço, the final settlement of note on the Portuguese side of the River Minho, a lush green world unfurls in dips and hillocks occasionally fanning around clusters of red tile roofs, that vary in size and purpose — from small, granitic hamlets to metropolises rife with museums, galleries, churches, castles, parks and palatial estates. Our activities took on a zigzag pattern alternating among visits to fortified towns, crisscrossing the river Minho, from Portugal to Spain and back again, dipping south to the grand historic cities of Braga and Guimarães, or winding like limp spaghetti over the lumpy massifs of Peneda-Gerês.

All the while the Hotel Minho proved itself the perfect headquarters, a nucleus of quiet where we could relax in the spa or refuel in the adjacent restaurant called Braseirão before plunging into the next day's activities. The restaurant is owned by the same people who own the Hotel Minho. Menus feature typical regional fare such as appetizers of fat black olives, figs from the restaurant's garden and crusty breads. Entrees include polvo (octopus), alheiras (porkless sausage invented by the Jews during the Portuguese Inquisition) or cabidela (chicken cooked in its own blood and more delicious than it sounds).

Duly fortified we broke up the driving tours with outdoor activities that were easily accessible from the hotel. One morning we hopped on bicycles supplied by the hotel and pedaled west toward Valença. With the River Minho on our left, the Spanish shore seemed an Olympic pool's length away — we could have swum across — while on our right groves of oak and other deciduous trees provided dappled shade among cornfields and a small marina. A woman in traditional black herded her goats along a leafy offshoot.

We spent the afternoon at Moinhos da Gávea, an old water mill that's been turned into a park and recreational center. Guides from Elos da Monha then took us on a hike along a mountain trail to the ruins of an ancient watchtower, now overgrown with ferns and ivy, that overlooks the islands of the Minho estuary. We later kayaked to some of these islands, guided by Agostinho of Animaminho, an outfitter located next to the old fortress of Cerveira.

On days we weren't hiking, kayaking or bicycling, we eagerly lapped up Francisco's expert guide service, his stories and his surprises. "The most beautiful thing is to be surprised," he said as he shared his knowledge of Minho and its wonders. In Viana do Castelo, the mossy, pocked remains of a little-known monastery, now roofless and overgrown with vines, still tugged at his sensibilities. "I was so emotional the first time I came here," he said. "Look, even in ruins it is lovely."

In Guimarães, he led us through the 15th century palace of the Dukes of Braganza and the thousand-yearold castle from which Afonso Henriques, the first King of Portugal, launched the Reconquista against the Moors. Francisco related the story with a pride that was as touching as a hymn of praise. And at the nearby Monastery of Tibães, he had a twinkle in his eye as he pointed out the purposeful flaws — mismatched arms of chairs and other surprises — among the effusive rococo decorations and gilded carvings. Apparently the workers were jealous of the credit given to the masters for work they didn't do, so deliberately desecrated their own workmanship. "You see," said Francisco, "another surprise, although maybe in this case it is not so good."

A better surprise was a trip into the heartland of vinho verde territory near Monção where green-skinned alvarinho grapes hang from trellises to avoid fungal diseases before they are crushed into the popular wine. Verde means green or young, a reference to the light-bodied taste of the wine, not the color, which is closer to a pale golden shade somewhere between lemons and wheat.

We stopped at two wineries, the palatial Palácio da Brejoeira, where, at the time of this writing, the matron, in her late 90s, still lived and supervised production (the gardens and parts of the house are open for tours); and at the Quinta Vale dos Ares, run by Miguel Queimado, a recent convert to the industry. According to Miguel's father, chemical engineer Alberto Queimado, the Vale dos Ares wines differ from the typical vinho verdes in that they are grown predominantly on schist (as is Port in the Douro region) instead of the usual granitic soil along the River Minho.

It was drizzling gently when Francisco drove us to the airport in Porto. "Is it always foggy this early in the morning?" I asked. Francisco smiled and said, "This is the greenest part of the country because there is water everywhere. Remember we are in this world to be surprised and you will see, when we get to the airport there will be sunshine. Our aim is to fi nd balance and so we need both sunshine and rain. When we have balance, happiness comes as a bonus."

Our week in Minho had ended as it began — with a surprise.

- Apartments, Housing, and Real Estate

- Automotive Sales & Leasing - Cars, SUVs & Trucks

- Clothing & Apparel

- Communications & Technology

- Concierge Services

- Contracting

- Dining & Entertainment

- Education

- Event Planning Services

- Financial Services

- Health & Beauty

- Home Furnishings

- Hotels & Accommodations

- Insurance

- Medical & Dental Services

- Office Services

- Property Management

- Security Services

- Shipping & Moving Services

- Specialty Services

- Travel & Transportation