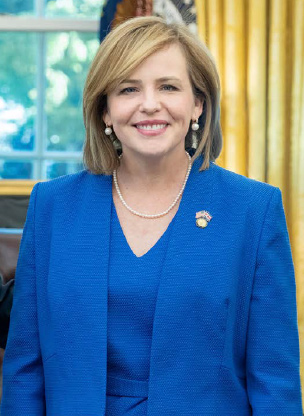

H. E. Dr. Catalina Crespo-Sancho

Costa Rica is one of Latin America and the Caribbean’s most politically and economically stable countries. Like other nations, it is recovering from COVID and the spillover from the pandemic’s damage to the global economy. At the same time, it is facing the challenge of the human flood of refugees from its neighbors, and the increase in narcotrafficking and organized crime that comes with it—all while repairing damage to its once pristine environment caused by a population increase and the mixed blessing of mass tourism. But the good news is that the Costa Ricans are proving better at tackling these and other challenges of the moment than others in the region, thanks in part to solid democratic foundations.

Costa Rica is one of Latin America and the Caribbean’s most politically and economically stable countries. Like other nations, it is recovering from COVID and the spillover from the pandemic’s damage to the global economy. At the same time, it is facing the challenge of the human flood of refugees from its neighbors, and the increase in narcotrafficking and organized crime that comes with it—all while repairing damage to its once pristine environment caused by a population increase and the mixed blessing of mass tourism. But the good news is that the Costa Ricans are proving better at tackling these and other challenges of the moment than others in the region, thanks in part to solid democratic foundations.

The country has a long history of welcoming people in need of international protection. According to Costa Rica’s ambassador to Washington, Dr. Catalina Crespo-Sancho, in a recent interview with Diplomatic Connections, her country is fourth in the influx of displaced people in the region. Between 1,000 and 2,300 a day crossed the border earlier this year from a higher rate in 2023 of 3,000 daily, with most coming from Venezuela and Nicaragua. But Ambassador Crespo-Sancho says that for many refugees, Costa Rica is a stopover “to rest,” taking advantage of the country’s proffered economic help, access to education, health, and social protection.

Costa Rica uses police to protect its borders because the country has not had a standing army since the late 1940s when shrewd civilian politicians disbanded the Costa Rican armed forces primarily to make the government safe from the threat of military juntas, widespread in the region at the time. The de-militarization freed up resources for public education and a cradle-to-grave medical and social program that remains unique in that part of the world. Other countries in the region have since disbanded their national military, including Dominique, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent, The Grenadines, Haiti, and Panama.

Washington is Ambassador Crespo-Sancho’s first diplomatic appointment, but not her first time working in the Nation’s Capital. She has held posts at both the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank focusing on development issues in Latin America and Africa, held U.S. professorships at Columbia University and the University of Georgia, and worked on immigrant issues in her own country.

Diplomatic Connections: Your official biography describes you as “a human rights specialist with over 20 years of experience in international development.” How does that lead to the key post of your country’s ambassador in Washington as your first diplomatic appointment?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: This is my first diplomatic post. But I have worked with international organizations all over the world. When you work with different governments it gives you a background in how to negotiate, how to get a win/win for everyone—and that’s what a diplomat should do, right? The best negotiations are when two countries or more benefit from whatever is negotiated. In that sense, my past has prepared me for this job, and I’m very thankful that the president (Rodrigo Chavez Robles) chose me to do it. I’ve had a long-standing relationship with the U.S. in one way or another. I was living in the U.S. for a long time, and though I was never involved in politics - I was learning how society acts.

Diplomatic Connections: What do you see as your main mission as ambassador?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: As ambassador I need to strengthen U.S. relations with Costa Rica. That’s the first thing. And the second thing is to see that the U.S. understands that it pays to do the right thing. Costa Rica is democratically stable, we respect human rights, we are environmentally responsible, we do all these things, but then maybe you don’t get as much attention. I think that’s human nature. Sometimes when you’re well behaved—then maybe you’re not as much noticed. The relationship has always been good, and in the last year it has gotten better. One reason was an official presidential visit: there had not been an official visit to the Oval Office for 15 years.

Diplomatic Connections: Is there anything you would like the United States to do that it isn’t already doing?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: Sometimes, if you’re the U.S. you forget that even countries that are doing well need more help, for example, in security. Costa Rica has been among the countries that are secure, and safe. It has no army. However, that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t need help—the whole region needs help. We have been getting security help from the U.S. but that’s an example of things that haven’t been as strong as they should be.

Diplomatic Connections: What advice would you give to a fellow diplomat, newly arrived in Washington, about working in this capital?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: I would say the first thing to do is to listen, to observe what’s going on, to look at how his or her country could benefit from what’s going on in the U.S. and how it could benefit the U.S. Secondly, getting to know people, getting to know men and women in the Congress—what do they feel, what are their areas of special interests. I would say the first thing is to observe…from the government, from the Hill, and the second one is what common interests we have. I would say the first thing is to observe how your country is perceived by the government, the people, and the Congress, and the second thing is to look at what common interests you have.

Diplomatic Connections: A recent OECD report says Costa Rica is “globally known as a green country and biotourism destination.” Then the report went on to add that tourism, urbanization, and population increase “have long strained” the underground waterways, and infrastructure services, and this is something that needs to be looked into. Does the OECD have a point here?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: In any country that’s growing, which is the majority of countries, the population is increasing, so yes, there has to be constant modernization of infrastructure. For example, water and electricity—in Costa Rica, 99 percent of our territory has electricity and it’s about the same with drinking water. Access to drinking water became part of the constitution a few years back, so it’s a right. Of course, there’s always a lot more to do. Both the current and previous governments have worked on them because also it’s about change in the world. For example, Costa Rica is also working on the IT infrastructure and AI.

Diplomatic Connections: As you say, there are always challenges—but more now than before?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: I wouldn’t say there are more challenges, but they’re different. Twenty years ago drug trafficking was not a challenge for Costa Rica. Now the whole Latin American region has a huge challenge of security. Another challenge: Costa Rica has always had lots of water. We’ve always acted responsibly with the environment. But what’s going to happen with the water? That’s a concern for the country because most of our electricity comes from hydro—93 percent, the only one of two other countries in the world that have that. So those are challenges we did not have 20 to 30 years ago, and we’re dealing with in one way or another. We’re going to be investing more in solar energy. And security, well, everything that comes in and out of the Atlantic and the Caribbean ports in Costa Rica gets scanned.

Diplomatic Connections: How is Costa Rica impacted by the current migration crisis—not a new challenge, but certainly intensified throughout the region?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: Yes Costa Rica is number four in the level of refugee applicants, after the United States, Germany, and France. That’s comparing us with huge developed countries. Last year, we received the highest numbers ever: about 3,500 immigrants a day crossed Costa Rica’s border. It went down, but it’s picking up again. In December and January, it was about 1,000 to 2,300, so immigration is a big fiscal strain. There are neighboring countries that send them in buses, and sometimes when I would talk to them, the families would say, “We don’t have money, so we come to Costa Rica to make money, and we come to rest.” Families could stay up to a month; Costa Rica provided food, and if they were under 18 or pregnant, they would be housed free in hostels.

Diplomatic Connections: Isn’t this part of Costa Rica’s advanced health system and social programs? Isn’t it a fact that some 80 years ago you abolished your military and invested the money in this level of social assistance?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: Of course, it is, at least part of it. Costa Rica abolished the military in 1948, and military spending is a lot of money. So we could spend 8 percent on education, and that is a big plus. That’s why, for example, companies like Intel, Amazon, and Boston Scientific, came to Costa Rica—why Intel has been there for over 25 years—because the skills they find in Costa Rica they don’t find anywhere else in Latin America. And the reason why is the investment in education that has been there for a very long time. Eight percent of GDP is really high.

Diplomatic Connections: Without an army how does Costa Rica deal with national security, defense, and border control?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: We have special police forces whose training is very different. The military is not always in charge of a country’s security; that’s managed by regular police forces. If you’re going to war, then you need the military. For environmental issues and helping the population we have police, but also have emergency committees that help.

Diplomatic Connections: You live in a rough neighborhood, historically very volatile. Again, without a military how do you deal with any disputes with your neighbors?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: I get the same questions from military personnel. They can’t imagine how it works, and it is very hard to understand. We have civilian-trained police as opposed to military trained, so we have a border team, and an immigration team. We do have complicated neighbors. About 10 to 15 years ago, we had a strong issue with Nicaragua about the border. We sent the police to the border, but we decided to go the diplomatic route so we took the case to the International Court and that helped Costa Rica. We try to use the diplomatic way as much as we can. Until now I can’t give you an example when we needed to ask for help or support. It’s the way that Costa Ricans think about freedom and democracy, and the way that 5.2 million people have been educated throughout their lives. I grew up — and every Costa Rican child grows up — in the school system, hearing the importance of democracy and the importance of the environment. Which is why 58 percent of our country is protected land, and why Costa Rica is one of the few countries where compared to 50 years ago, today we have more forest coverage. That rarely happens. This isn’t one government coming in and deciding all this—this is a way of living. The only way of doing things. This is how I grew up, how my parents grew up, and how my kids grew up. That means that for every person in the country, that’s part of our identity.

Diplomatic Connections: What is the level of Costa Rica’s relationship with China?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: Costa Rica has relations with China, but also with most other countries. However, we are closer to the United States and most of our private sector companies come from the United States, so it’s a matter of proximity, but also of employment, who supports the private sector. But that does not mean that Costa Rica can’t have good relations with any other country. We try to have good relations with everyone.

Diplomatic Connections: The number of women ambassadors to the U.S. has been growing, and is now over 50 out of about 197. As a result of this, the U.S. State Department has now appointed a dean of women diplomats alongside the long-standing post of dean of the diplomatic corps. Is there that much difference between the requirements of male and woman ambassadors?

Ambassador Dr. Crespo-Sancho: Yes. I don’t know about ambassadors per se, but I do know about women in leadership positions generally. My specialty is conflict prevention, and I know that when there are women at the negotiating table the search for a solution will persist for longer, and also the outcome will be more helpful to society in general. When there are women at the table the outcome from the negotiations will be more helpful for both sides in general. My question is, when women and men work at the same level do they have the same opportunities, and I think the answer is no. But I’ve known fantastic men ambassadors and fantastic women ambassadors, so at a diplomatic level I wouldn’t have an answer to that one.

- Apartments, Housing, and Real Estate

- Automotive Sales & Leasing - Cars, SUVs & Trucks

- Clothing & Apparel

- Communications & Technology

- Concierge Services

- Contracting

- Dining & Entertainment

- Education

- Event Planning Services

- Financial Services

- Health & Beauty

- Home Furnishings

- Hotels & Accommodations

- Insurance

- Medical & Dental Services

- Office Services

- Property Management

- Security Services

- Shipping & Moving Services

- Specialty Services

- Travel & Transportation